What Is Emotion? Exploring the AV and PAD Models of Emotional Space

It is the nervousness before an exam, the joy of reunion, the loneliness and melancholy of sleepless nights.

Human emotions are so rich and variable—so how have scientists managed to quantify and model these subjective experiences?

Today, let’s explore a central thread in the development of affective science: from the earliest discrete emotion models, to the now mainstream AV model (Arousal–Valence), and then to the more refined PAD model (Pleasure–Arousal–Dominance).

Discrete Emotional Space: Six Basic Emotions

In the 1970s, American psychologist Paul Ekman proposed the famous theory of basic emotions.

His view was that human emotions are like “primary colors”—there exists a limited set of universal, basic emotions shared across individuals and cultures. Ekman initially identified six: happiness, sadness, anger, fear, disgust, and surprise, and later added contempt.

This categorization is intuitive and easy to grasp. In daily communication, we indeed use these words frequently to describe emotions. Ekman’s theory even influenced the development of facial recognition technology: by analyzing facial muscle movements, one could detect whether a person was “happy” or “angry.”

However, problems soon emerged:

- Human emotions go far beyond these few categories. For example, how should we classify “nostalgia,” “shame,” or “envy”?

- Emotions are not isolated “boxes” but rather continuous and blendable. The boundary between “surprise” and “happiness,” for instance, isn’t always clear.

- Emotional expression may also vary across cultures.

This led scientists to realize that relying solely on discrete classification to understand emotion was somewhat limiting.

Two-Dimensional Emotional Space: AV Model (Arousal–Valence)

To overcome the limits of discrete classification, psychologists began describing emotions in terms of continuous dimensions.

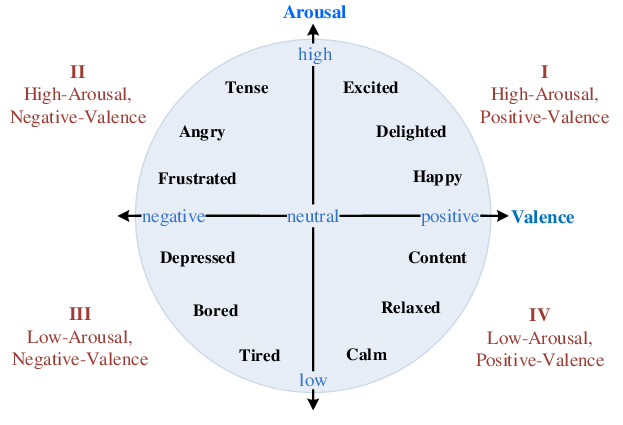

In 1980, psychologist James Russell introduced the Circumplex Model of Affect, better known today as the AV model (Arousal–Valence).

He discovered that nearly all emotions could be mapped onto a two-dimensional plane:

- Valence: the positivity or negativity of emotion (pleasant–unpleasant)

- Arousal: the level of physiological activation (high–low)

Examples:

| Emotion | Valence | Arousal |

|---|---|---|

| Happiness | High | High |

| Calmness | High | Low |

| Anger | Low | High |

| Sadness | Low | Low |

Through these two dimensions, we can represent the quality and intensity of most emotions. For instance:

- Excitement ≈ positive valence + high arousal

- Depression ≈ negative valence + low arousal

The strength of this model lies in moving beyond “isolated labels.” Emotions are now continuously distributed on a plane, allowing for gradation and transition.

But it also has limitations: some emotions occupy nearly the same spot on the AV plane—for example, anger and fear. Intuitively, we know they are different, but in two dimensions, it is difficult to distinguish them.

Three-Dimensional Emotional Space: PAD Model (also called AVD Model)

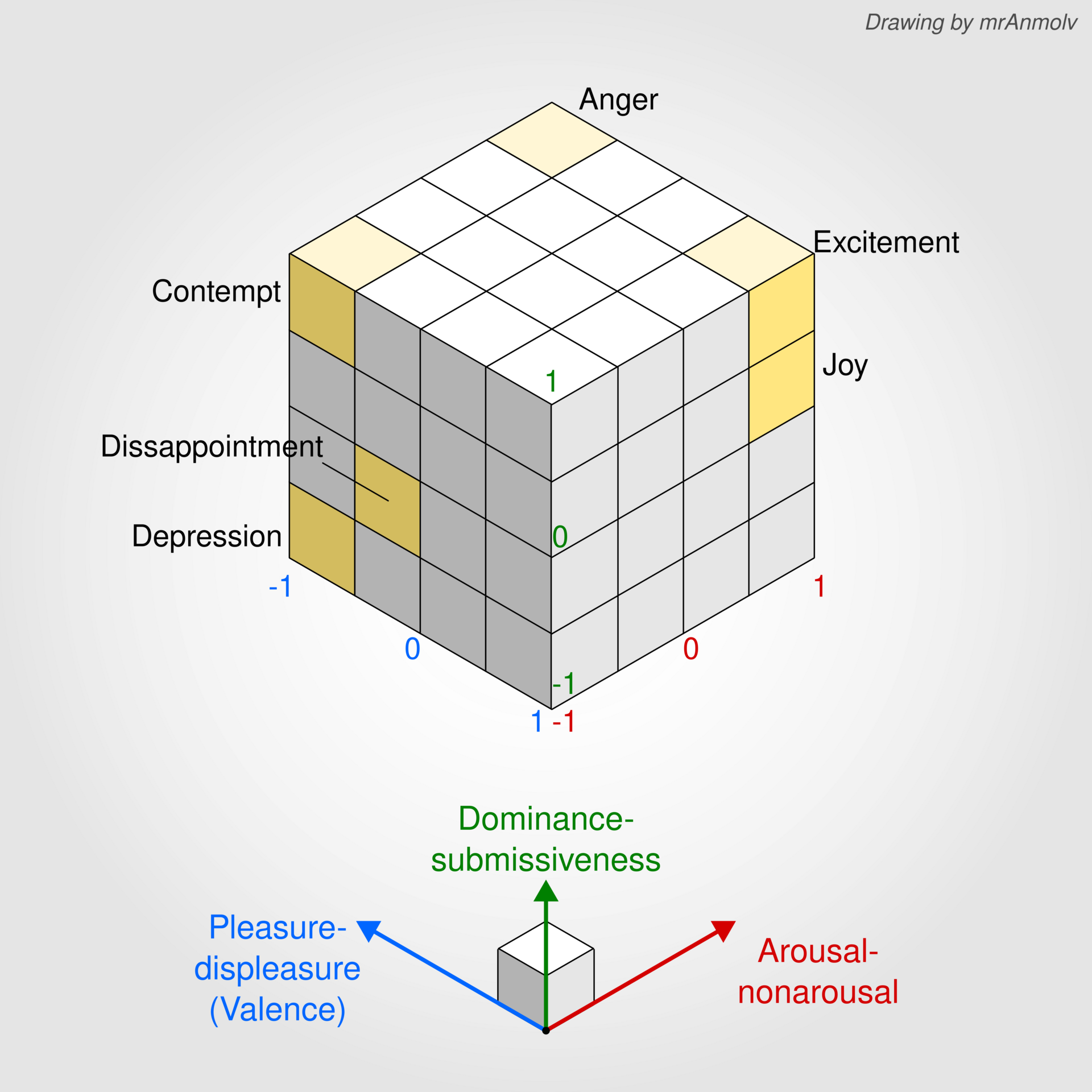

To better differentiate complex emotions, psychologists Mehrabian & Russell (1974) extended the AV model by adding a third dimension, forming the PAD model:

- P – Pleasure: pleasant vs. unpleasant (roughly equivalent to Valence)

- A – Arousal: excited vs. calm

- D – Dominance: the degree of control an individual feels in a situation

Since Pleasure is nearly equivalent to Valence, the model is sometimes referred to as the AVD model (Arousal–Valence–Dominance).

Examples:

| Emotion | Pleasure | Arousal | Dominance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anger | Low | High | High |

| Fear | Low | High | Low |

| Calm | High | Low | High |

| Sadness | Low | Low | Low |

| Joy | High | High | Medium–High |

Here we see that while anger and fear nearly overlap in the AV model, Dominance separates them in the PAD model:

- In anger, we feel “in control” (high dominance).

- In fear, we feel “overpowered by the environment” (low dominance).

Later, Bradley & Lang (1994) popularized the PAD model as a measurement tool through the Self-Assessment Manikin (SAM), making it widely applied in psychology, neuroscience, and affective computing.

Comparison of the Three Emotional Space Models

| Model | Core Idea | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discrete Emotion Model | A limited set of basic emotions | Simple, intuitive, cross-cultural | Cannot express continuity or mixed emotions |

| AV Model | Valence + Arousal | Captures continuous emotions, easy to quantify | Cannot distinguish emotions differing in control |

| PAD Model (AVD) | Pleasure + Arousal + Dominance | Most comprehensive; captures control differences | More complex, harder to measure |

Summary and Outlook

From discrete categories of basic emotions, to the two-dimensional AV model, and then to the three-dimensional PAD model, science has increasingly moved toward a spatial understanding of emotion—emotions can be seen as coordinates rather than fixed labels.

This spatial approach allows for a more nuanced analysis of emotional intensity, direction, and sense of control, while also laying a foundation for fields such as neuroscience, affective computing, psychotherapy, and research on music and emotion.

Looking ahead, with the development of physiological signal technologies such as EEG and ECG, we may even be able to map a person’s emotions in real time into this three-dimensional emotional space, and design intelligent interventions to regulate emotions—through music, meditation, or even AI conversations.

The scientific journey of understanding emotion has only just begun.

References

- Wikipedia. PAD emotional state model

- Ekman, P. (1971). Universals and cultural differences in facial expressions of emotion

- Ekman, P. (1992). An argument for basic emotions

- Russell, J. A. (1980). A circumplex model of affect

- Mehrabian, A., & Russell, J. A. (1974). An approach to environmental psychology

- Bradley, M. M., & Lang, P. J. (1994). Measuring emotion: The Self-Assessment Manikin and the Semantic Differential